Mapping Mexico: Telling Stories Untold

Maps tell stories of landscapes, communities, habitats, humans, wildlife, movement, and development. They can help us understand the places we care about. In an international organization, maps can also create shared understanding that may be more difficult to achieve across language and cultural barriers.

But mapping across cultures and borders can also illuminate gaps and divides.

As Wildlands Network has expanded its GIS capacity and mapping projects in Mexico, we have had to develop new ways of creating maps and adjust to different cultural norms and practices.

The stories below uncover how we have navigated this new terrain and how we’re leveraging the lessons we’ve learned for the good of Nature.

The process of mapping in Mexico is quite different than in the U.S.

The U.S. pours resources into data collection and scientific exploration, leading to a sometimes-overwhelming availability of data. Information on a single species could be collected by a variety of people, institutions, universities, and agencies. Data may conflict or be interpreted differently, but there is plenty of it to choose from.

In Mexico, the availability of data is much more limited. Generally speaking, a few public institutions hold most of the data, and university research data is often not publicly available. The data that is accessible can be too broad or insufficient to be conclusive.

For example, a national park in the United States has stark and even gated boundaries. The same boundary around some natural protected areas in Mexico can be hard to identify and may require extensive research.

Mexico has signed on to conserve 30% of its land by 2030, along with many other nations across the globe, as part of the legally binding Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiverity Framework. Keeping a tally of the nation’s progress and holding its government accountable is necessary to ensure progress toward this goal, and for that, accurate and publicly available information is essential. But, unlike in the US, no large-scale government effort to map protected areas has been completed.

Wildlands Network stepped up to create a high-quality map of protected areas in Sonora that advocates and decision-makers in Mexico can use as they work together to meet the 30 by 30 goal.

“When I set out to write about the natural protected areas in Sonora, Mexico, I assumed it would be straightforward to identify them,” reflects Juan Carlos Bravo, Conservation Programs Director at Wildlands Network. “I was wrong.”

“My approach to the project had to change very quickly when making an inventory just to figure out how many exist was a challenge. The project soon became creating a database that could answer basic questions such as: How many? Where are they? How big are they? When were they created? The numbers were hard to find and often inconsistent or insufficiently accurate for the standards of today,” he says.

After adjusting to the reality of the data, Juan Carlos set out to create a comprehensive, interactive map of all natural protected areas in Sonora. He worked with partners across the state of Sonora to collect as much data as possible, synthesize and standardize it, and then put forward the first comprehensive conservation map of the state.

The result: this map revealed to the conservation community and the Sonoran government that the state has a long way to go to reach 30 by 30 goals – only 10.6% of the land is protected in Sonora. However, it also showed that conservation lands do exist and can be models for future action.

Moving forward, Wildlands Network continues to update our Sonoran map with progress against 30 by 30 goals, creating a visual tool for putting pressure on the government to increase the volume of natural protected areas and accountability to ensure consistent and accurate reporting.

This map has also helped guide on-the-ground habitat protection as we identify conservation gaps and prioritize engagement opportunities.

When the government does search for new natural protected areas, we and our fellow conservation experts are poised to locate the most important areas to conserve for wildlife movement and biodiversity. This is the power of Wildlands Network’s conservation mapping in Mexico.

El Aribabi Conservation Ranch, a biodiversity hotspot near Ímuris in Sonora under private conservation

Cultural divides can be stark. In northern Mexico, Wildlands Network quickly realized that when reading a map, we are not all using shared language.

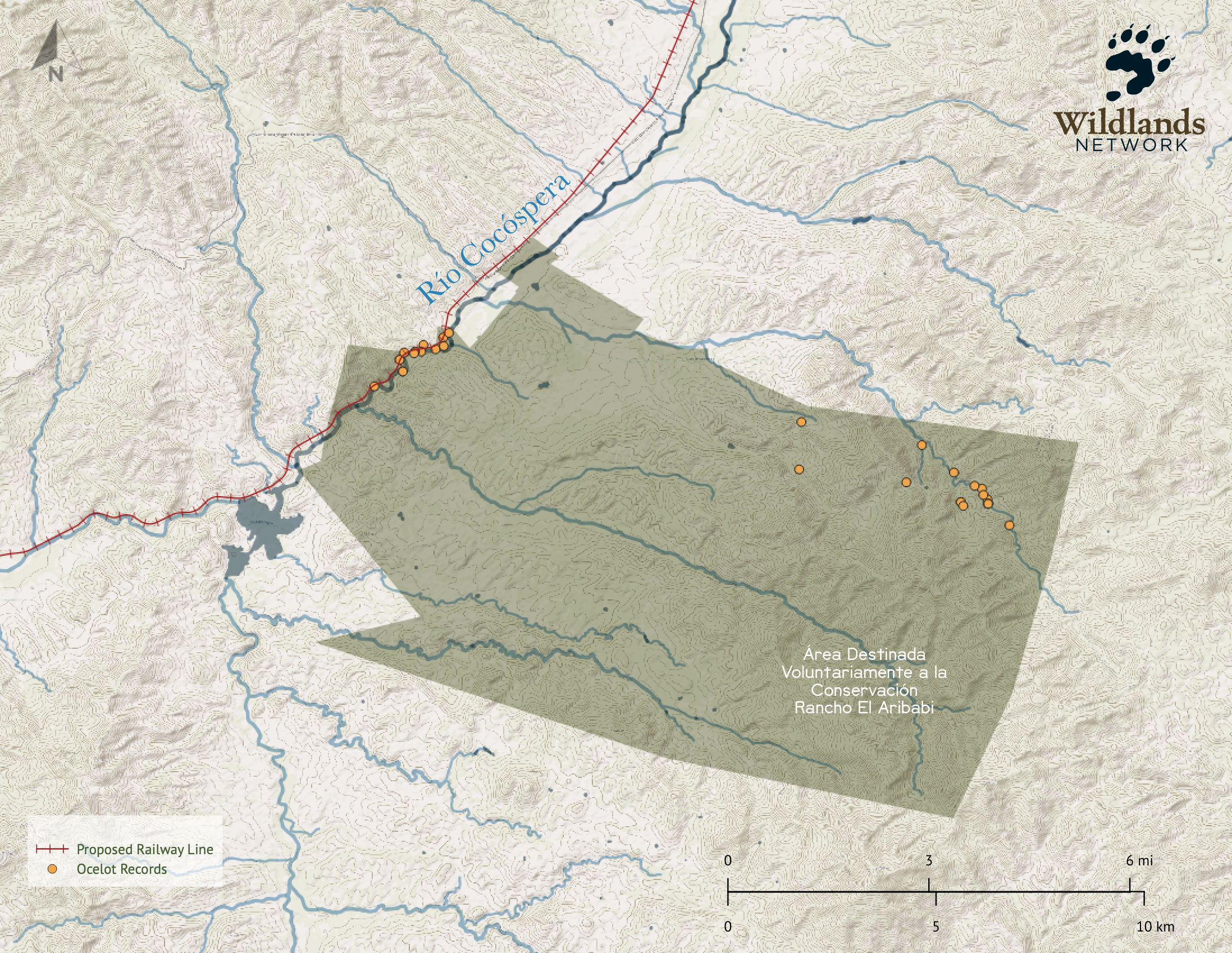

In the Sierra Azul-El Pinito corridor just east of the town of Ímuris in northern Mexico, Mexican agencies and developers looked at topographical maps of the land to find a path of least resistance for the construction of a new train. On their maps, they saw flat land away from most urbanization through Ímuris and up to the Nogales-San Antonio road. Where Wildlands Network and our Mexican allies saw unbroken habitat to be left undisturbed, they saw unobstructed, undeveloped land – perfect for constructing new infrastructure.

Unlike how we read maps, these officials didn’t recognize the stories their maps were telling about the rivers and the wildlife.

What we know: the land is flat due to some of the best-conserved sections of the Cocóspera River, which winds directly through the proposed train route. While the land may be flat, the presence of this river means building on top of floodplains at best and destroying whole riparian forests and wetlands at worst, making for an extensive and expensive engineering feat, let alone a senseless destruction of some of the precious few year-round water sources in this otherwise arid landscape.

Wildlands Network staff realized that we needed more robust maps, with more data and more information. We needed maps that made clear to anyone, not just those working in conservation, that unbroken landscapes contain a wealth of species and are the foundational building blocks for every other conservation action.

So, we created new maps that told a different story of the proposed location of the train.

Each simple orange dot is bursting with rare and precious information about wild cats: jaguars and ocelots. Like many species, information on jaguar and ocelot population is hard to find anywhere, especially in northern Mexico. To overcome these hurdles, Juan Carlos, Mirna Manteca, our Northwest Mexico Program Co-Director, and other conservation non-profits collaborated to collect existing data and generate refined, site-specific data on felines in Sonora.

While there is still much to learn about these creatures, experts have identified their locations and movement patterns with camera traps and modeling tools. When seen on the map, it becomes clear that jaguars, who are for the first time in decades returning to their once-native lands in the United States, are likely doing so through the Sierra Azul-El Pinito corridor where the train route is proposed. In our maps, the corridor isn’t empty – it's alive and essential.

In creating these maps, we also started to understand more about the potential impact of the train.

We learned that ocelots like to be near the unobstructed Cocóspera River’s edge, meaning that if a train cuts through the river, it also impacts these endangered and federally protected cats. In a world where humans have become disconnected from wild places and other animals, a map can be the bridge to a new understanding of place.

“With this knowledge comes empowerment,” Mirna says. “We showed these maps to the Ímuris community so that while fighting a battle against this development, they can understand the wildlife that lives in their backyard, the other lives that they are fighting with and for.”

As we continue to support and empower local communities to protect and restore the wild lands around them, we will continue to use maps to communicate stories of the wild and stories of conservation to wider audiences. With their help, we will create a shared vision of how to reconnect, restore and rewild communities across North America, one map at a time.