Looking for martens in high places

This project started more than four years ago on a camping trip in the San Juan Mountains of northern New Mexico. Most commonly associated with Colorado towns like Silverton, Telluride, and Durango, these mountains extend into northern New Mexico where at 10,000 feet above sea level they serve as foothills to the jagged, rocky peaks that define the range.

Western senior biologist, Aaron Facka, and I were both new in our roles at Wildlands Network when we decided to meet up for a couple of days to spend some time in the field and get to know one another. We chose the Greater Cruces Basin region — named for the 19,000-acre Cruces Basin Wilderness that occupies the heart of New Mexico’s San Juan Mountains, just south of the Colorado border on the Carson National Forest. While still relatively unknown, the region holds countless natural resource gems. In addition to serving as the headwaters of numerous streams that feed the Rio Grande and Rio Chama, it boasts recently identified migration corridors for elk and deer, provides summer range for the highest elevation population of pronghorn in North America, is home to genetically pure populations of Rio Grande cutthroat trout, and even hosts a section of the Continental Divide Trail.

Over the course of a few days, we drove Forest Road 87 from the shadows of San Antonio Mountain on the Taos Plateau northwest, across the Brazos Ridge and its views of Great Sand Dunes National Park and the 14,000-foot Blanca Peak, through open meadows and aspen groves to the Colorado border.

At one point, we stopped in a dense stand of timber giving a break to both our bodies and our trucks’ suspension. “This looks like marten habitat,” Aaron said. Like other mustelids, a family of carnivores that includes weasels, badgers, fishers and wolverines, Pacific marten (Martes caurina) prefer mature forests with high canopy cover and lots of downed woody debris. The canopy cover keeps them hidden from aerial predators like hawks and owls, while thickets of downed trees give them an advantage while hunting their prey. This was exactly the kind of habitat they needed to thrive.

From there, the project was born

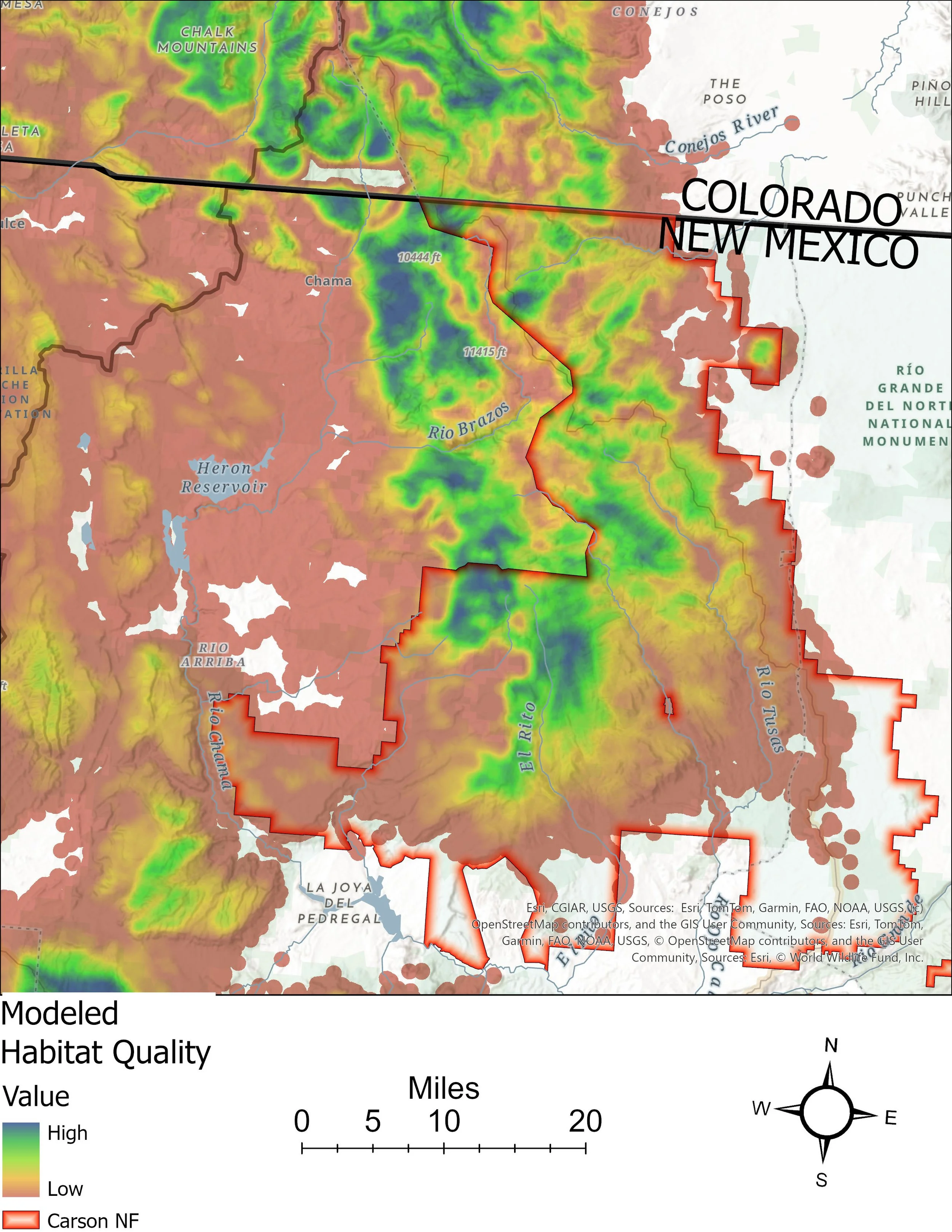

Following that trip, Aaron developed a habitat model for marten across New Mexico’s San Juan Mountains, and in the summer of 2022, in partnership with Defenders of Wildlife, we deployed 40 cameras across the range in areas identified by the model as strong habitat. At first, our main study questions were basic. New Mexico is the southern extent of the Pacific marten’s historic range, and because there had not been any recent surveys in the San Juans, our first goal was to simply confirm their presence.

Habitat quality model for marten across New Mexico’s San Juan Mountains. Created by Aaron Facka/Wildlands Network.

Fortunately, that did not take long. A couple of months after deploying our first cameras, we captured shots of martens at multiple sites, and the following year we deployed another 30 cameras expanding our study area. By the spring of 2024, we had confirmed the presence of martens in multiple distinct clusters from the Colorado border to areas about 30 miles south, in addition to thousands of pictures of non-target species, including red fox, badger, porcupine, black bear, mountain lion, bobcat, elk, dusky grouse, and even a ringtail!

By 2024, our research questions had become more complex. Yes, martens are present, but what is the status of this population? How abundant are they? Do they exist in isolated clusters or are they connected to each other as well as martens further north in Colorado where their population is believed to be robust? If they are isolated, what factors are limiting their connectivity — roads, logging, fires?

Taking the next steps

During the 2024 field season, we expanded our cameras from the Carson National Forest to some strategically situated private land areas between the clusters of martens we had already detected and were able to detect a few additional martens. We also made plans for our next steps — genetic testing.

Photo by Wildlands Network

Genetics could potentially paint a much more detailed picture of the status of these animals and start to shed light on our finer scale questions regarding martens’ population dynamics. To collect the samples, there were a couple different methods we considered. Capturing animals to collect hair samples would be the only way of being assured every sample came from a marten, but it’s time and resource intensive, and handling animals always comes with risks (and additional permits). Hair snags (baited boxes with brushes or glue strips meant to snag hair of passing animals) were another option — less risk to the animal, but still time intensive and a high likelihood of getting samples from non-target species like long and short-tailed weasels, chipmunks, and more.

The last option was detection dogs. Instead of hair or live animals, detection dogs are trained to sniff out scat of target species, and they have become increasingly common for a wide variety of species from salamanders to whales. And lucky for us, there was a team based in southern Colorado whose dogs had significant experience with martens.

Photo by Wildlands Network

Using our camera data and Aaron’s habitat model, we identified seven distinct areas in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico for the detection dog team to concentrate their surveys, and earlier this fall, we joined them for their first day in the field. We chose an area where our cameras had regularly detected martens so that we could get off to a good start, but the dogs were even more successful than we could have hoped.

Photo by Wildlands Network

With us following comfortably behind so that the dog and her handler could work without distraction, they found the first scat while still in view of the road! Over the next hour, we had barely made a quarter of a mile with her finding 10 additional scats, each time getting rewarded with a ball as her prize, spinning around with glee at successfully performing her job.

Photo by Wildlands Network

What’s Next?

The dogs will spend another two weeks in the field, collecting samples from each of the 7 areas where we expect martens to occupy. After that, we will send each scat sample to the Rocky Mountain Research Lab in Missoula, Montana, and patiently await results. Next steps will largely depend on what the genetics tell us, but already, we’re beginning to consider different possibilities:

Genetic Isolation

It’s possible that all or even some of the clusters of martens we’ve detected are genetically isolated from either each other or marten populations in southern Colorado. Depending on the nature of these patterns and how limited genetic diversity may be, one potential next step could include the translocation of martens from adjacent regions to increase genetic diversity. This would likely require additional testing and a deeper collaboration with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

Road Mitigation

If a lack of genetic diversity does appear to be an issue, we might also consider whether roads could be factor. There are two major highways that run through our study area. US-64 cuts through the heart of our study area, between the towns of Tierra Amarilla and Tres Piedras in New Mexico. Further north, CO-17 bisects large blocks of habitat between the Colorado-New Mexico border and Colorado’s South San Juan Wilderness. Both highways see relatively little traffic and are not a significant barrier for larger species like elk and deer, but for martens, which tend to avoid areas without canopy cover, these highway corridors could be preventing important north-south movement. If the genetic data does support this hypothesis, we might begin new, more focused camera study on those road segments to better understand where animals are trying to cross.

Forest Management

Even if the lab results indicate a genetically healthy population, that doesn’t mean martens are out of the woods. Before working with detection dogs, we initiated a partnership with the Frey Lab at New Mexico State University to explore how different forestry treatments, such as fuels reduction projects, might impact habitat use by martens and other species like red fox, snowshoe hare, dusky grouse, ermine and black bear. Regardless of the population’s current status, because they depend on mature forests with lots of downed, woody debris — the exact kinds of forests that are being prioritized for thinning and fuels reduction projects — there’s concern that these kinds of habitats could be at risk. With these questions in mind, this partnership will aim to pick up where our camera study left off by taking a more detailed look at how these species’ occupancy overlaps with different vegetative regimes, including areas that have been logged or thinned in the past.

More than four years have passed since the camping trip and the long, bumpy drive along one of New Mexico’s worst (but prettiest) roads that inspired this project. We are far from the end, but we are at the end of the beginning. We’ve successfully confirmed that martens have persisted in New Mexico’s San Juan mountains, but whether they’re still thriving or merely hanging on in small, isolated pockets remains to be seen. The good news is that we’re in it for the long haul with numerous possibilities for future research and restoration still in front of us, including more focused road ecology research or even population augmentation.

Photo by Wildlands Network

In the meantime, we’re finding other ways to maintain the integrity of this unique ecosystem — closing illegal roads, ensuring livestock fencing meets wildlife-friendly standards, and coordinating with organizations engaged in watershed restoration activities. From trout to martens to migrating pronghorn, Wildlands Network is committed to protecting and restoring this majestic landscape one step at a time.