Making Utah's Fences Safer for Wildlife: A Conversation with Kasey Lindstrom

Across Utah, efforts are ongoing to make fences safer for wildlife and to improve large-scale habitat connectivity. Mapping fences is an important step towards reducing and removing barriers to wildlife movement.

To support these efforts, Kasey Lindstrom (Utah Project Manager), in partnership with Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (UDWR) and Sageland Collaborative, has been developing fence mapping guidelines to help ensure high-quality and in-depth data collection statewide. These guidelines will help identify and prioritize fences for improvement.

In this Q&A, Kasey answers questions about these guidelines — what they are, why they matter, and how people can get involved in the work to make Utah’s landscapes more connected for wildlife.

WN: Before we get into the guidelines, can you talk about why fences matter so much for migrating wildlife and what Wildlands Network has been doing on this issue?

Kasey: Absolutely. Across the West, thousands of miles of barbed wire fence crisscross the landscape to manage livestock and divide rangeland. What seems like just a few strands of wires to us can be a deadly barrier for migrating wildlife like mule deer, elk, and pronghorn. Fences can cause injury and even death — high top wires can trip up adult animals, low bottom wires can trap fawns and calves, and tight spacing between top wires can entangle hooves and antlers.

The Paunsaugunt mule deer herd in southern Utah is a notable example. Each year, the herd migrates from their summer range in the high-elevation plateaus near Bryce Canyon National Park and their winter range in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. This migration is essential for the herd — it’s how they escape deep snows and access the resources they need throughout the year. However, fence after fence blocks their way, turning what should be a natural migration into a dangerous obstacle course.

At Wildlands Network, we’ve been working to fix this problem by surveying and mapping existing fences to identify which ones are most likely to disrupt wildlife movement. Then, we either retrofit fences to be more wildlife-friendly or remove fences altogether with the goal of reconnecting large landscapes and removing barriers in important migration routes so wildlife can move more freely and safely.

WN: Why are these guidelines necessary?

Kasey: These guidelines are meant to improve consistency and clarity across all fencing projects throughout the Western Wildway.

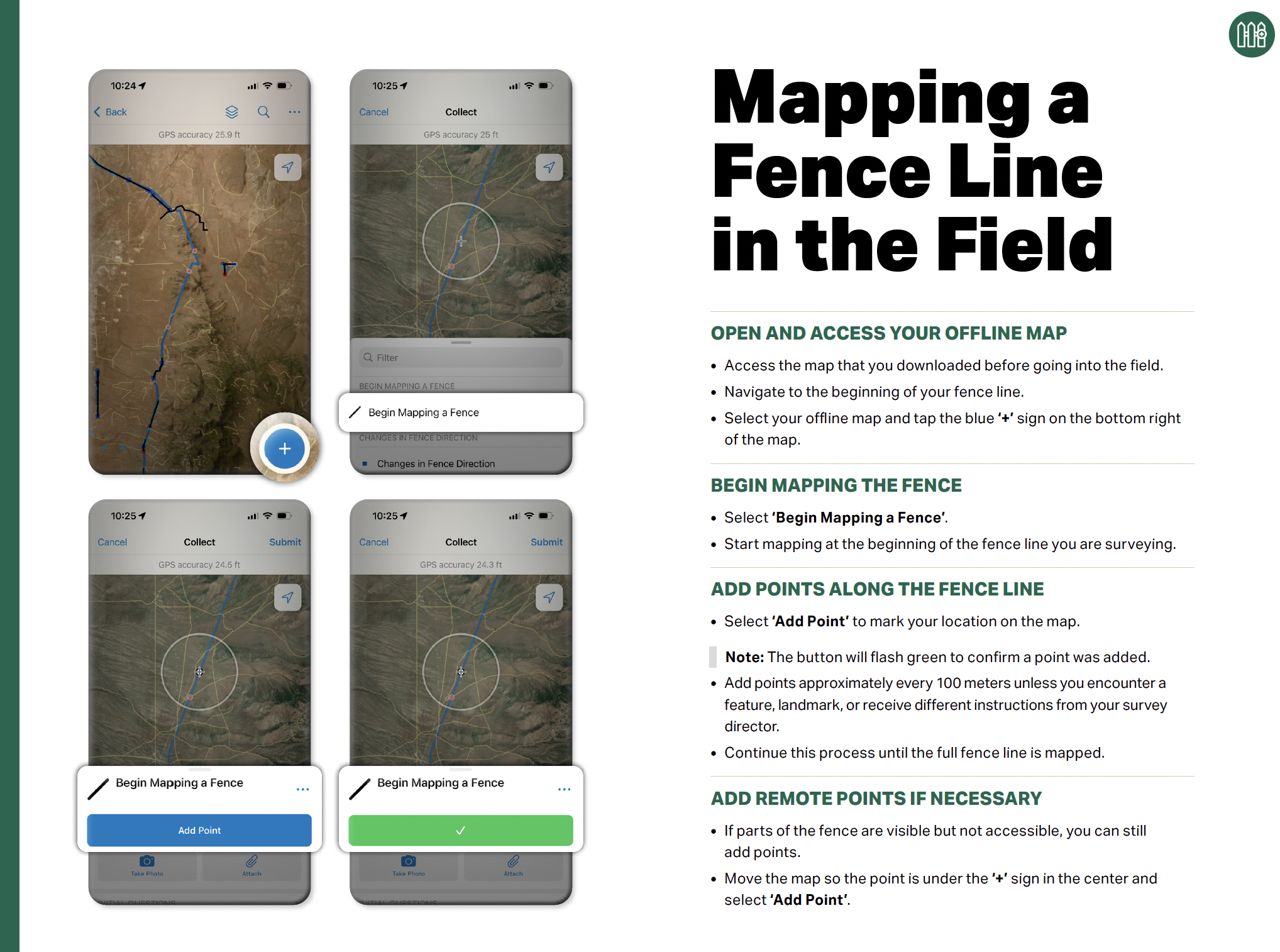

These guidelines help walk through how to use the app to record data accurately and efficiently, from fence location, condition, and materials to non-fencing structures, like cattle guards and gates, to wildlife found in or along the fence. These guidelines make it possible for anyone — whether volunteers and community members, agency staff, or partner wildlife organizations — to engage in on-the-ground surveying and mapping effectively. This ensures that the data is not just thorough but also reliable so that decisions about which fences to improve are based on solid information.

Ultimately, these guidelines ensure that every effort, whether small or large, is coordinated and cohesive and that each and every participant is well-equipped to survey and map.

WN: Where do these guidelines fit into the bigger picture of the work WN and its partners are doing?

Kasey: At the heart of Wildlands Network’s mission is the idea of connectivity, and these guidelines are a part of the larger effort to make landscapes more permeable and connected for wildlife across Utah, the Western Wildway, and North America. It’s understandable that fences seem insignificant when compared to major highways and housing developments, but they are one of the most pervasive barriers that animals face — just one poorly designed or maintained fence can have devastating impacts on an individual animal or even an entire population.

That’s why having a way to identify where fences are located is so important. Each survey helps us gather all sorts of information about fences, like condition, materials, and heights, which can tell us a lot about how a fence can impact wildlife. In short, these guidelines help inform us on how to connect habitats and make landscapes more permeable.

WN: How do you envision these guidelines being used?

Kasey: We envision these guidelines as a practical and accessible tool for anyone to use in the field — from land and wildlife managers to community members and landowners to hunters and other outdoor recreationists. Ultimately, the idea is to make it as simple and standardized as possible for people to survey fences, so that fences can be mapped consistently, efficiently, and at any scale.

WN: What’s next for WN’s fencing projects in Utah?

Kasey: There’s plenty of opportunities to improve fences throughout the state. Within the Paunsaugunt mule deer migration corridor alone, there’s still over 130 miles of impermeable fences in poor condition that continue to disrupt the herd’s movement year after year. We’re going to continue to chip away at problem fences within this important migration route.

WN: How can people get involved? Are volunteer opportunities on the horizon?

Kasey: Absolutely! Volunteers are an essential part of fence improvement projects and can help us by volunteering to survey, map, and inventory fences and retrofit or remove fences. If you’re interested in volunteering in any capacity, please feel free to contact me. There’s plenty of upcoming work all across the state — from the Paunsaugunt Plateau and southern Utah to the West Desert and Basin and all along the Wasatch Range and Uinta Mountains. No matter where you are in Utah, there’s important work to be done to make fences safer for wildlife. Even if you can’t volunteer in the field, you can still help by learning to recognize and report problem fences or by sharing resources, like these guidelines, with landowners and other stakeholders.