Overpass designs could give endangered bighorn sheep safe passage over a deadly California highway

Long before Interstate 8 cut through the Peninsular Mountain Ranges — the mountains west of Coachella and Imperial Valleys — desert bighorn sheep traversed the rocky terrain in search of food, water, and places to birth their lambs.

Today, I-8 and its vehicle traffic pose a devastating barrier for Peninsular bighorn sheep, an endangered population of the desert bighorn sub-species. One part of the highway is divided and encircles an area that bighorn visit to have and raise their lambs. When bighorn attempt to traverse the eastbound section of highway to and from that habitat, many are struck by vehicles. The highway has the second-highest mortality for bighorn in the state, just below a section of Interstate 74 within the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument.

But an effort is slated to bring needed relief for bighorn and other wildlife populations that live in the vicinity of the roadway. In 2023, the Wildlife Conservation Board granted $5.8 million to UC Davis to determine the design and placement of a crossing to safely usher bighorn and other wildlife across I-8 and protect motorists. Now, researchers have identified two priority locations for a potential crossing in the eastbound section of I-8, and are entering the feasibility and design phases to determine where the crossing will be built.

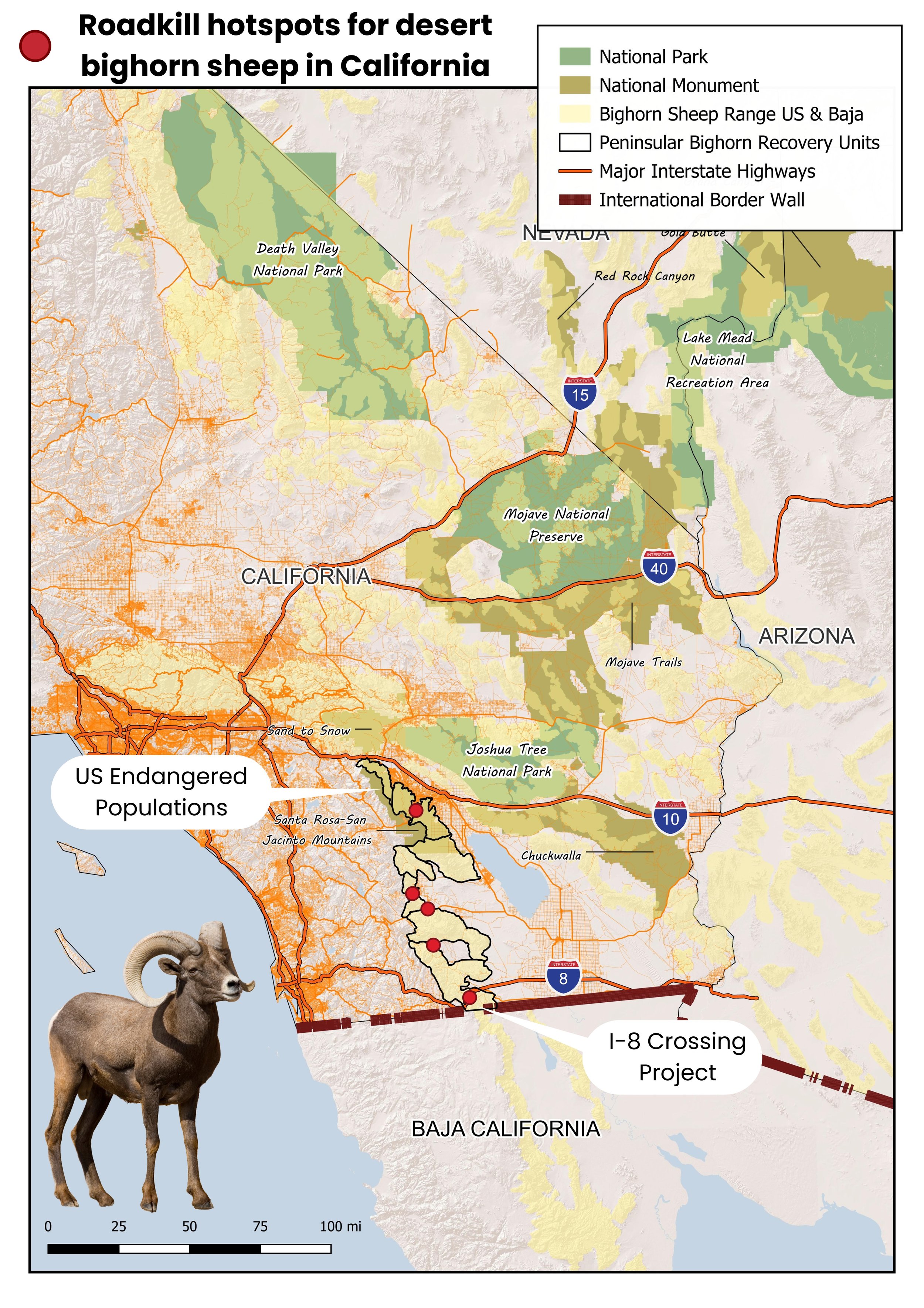

Caption: Top 5 regions for desert bighorn sheep vehicle-caused mortalities. Roads with the most documented bighorn-vehicle strikes all occur in the Peninsular Ranges where populations are endangered and at risk of isolation from surrounding populations. Human-built barriers such as highways, canals, and the US-Mexico border wall have reduced the safe movement paths available for bighorn populations to keep connected — a behavior critical for their long-term survival (Map created by: Christina Aiello, WN California Wildlife Biologist).

The project’s success requires broad collaboration from many groups. The core project team consists of staff from the U.C. Davis Road Ecology Center, Mark Thomas Engineering, Dudek, and Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, along with Wildlands Network. The team also works closely with state and federal partners, including the California Department of Transportation, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

There’s also a large list of organizations that voiced support for this project when we applied for funding. This project wouldn’t be off the ground without this additional community involvement.

Crossings prevent population decline

Bighorn populations run small, and interaction with neighboring populations is key to survival. In addition to mortality from vehicle collisions, roads can have more subtle, negative effects in the long term.

If this problem persists or gets worse where bighorn stop trying to cross I-8 entirely, it would permanently separate populations north and south of the highway and create two smaller, more isolated and more vulnerable populations. Less mingling of the two populations could reduce desert bighorn genetic diversity over time, which is critical for adaptability and resilience, according to Dr. Christina Aiello, California Biologist at Wildlands Network.

Caption: As deserts become hotter and droughts more severe, connected habitats become more important for species like bighorn sheep to move between to find enough water and food (Photo: Janene Colby, California Department of Fish and Wildlife).

A crossing will connect bighorn populations, and bolster the species against climate change. Though well adapted to dry desert conditions, more severe droughts are creating even drier conditions, with more time between rainfall. As temperatures rise, water becomes scarcer, forage becomes drier, and bighorn need even more water to counter heat stress.

Identifying potential crossings

Wildlands Network’s work involved looking at data from collared bighorn to analyze their movements and determine crossing locations.

We looked at where bighorn approach or spend the most time near the road, identified areas where there’s evidence of successful crossings, and where there’s evidence of unsuccessful crossings that result in sheep deaths, says Aiello.

Caption: Section of I-8 that intersects Peninsular bighorn sheep habitat and is being targeted for a wildlife crossing structure and fencing (Photo: California Department of Fish and Wildlife).

Animals in general tend to spend time close to sections of roadway that have their preferred habitat and resources, and where they feel safe. Even within preferred habitat, they may have preferred routes, similar to how humans commute — while there’s likely more than one way to go, people opt for a familiar, efficient path.

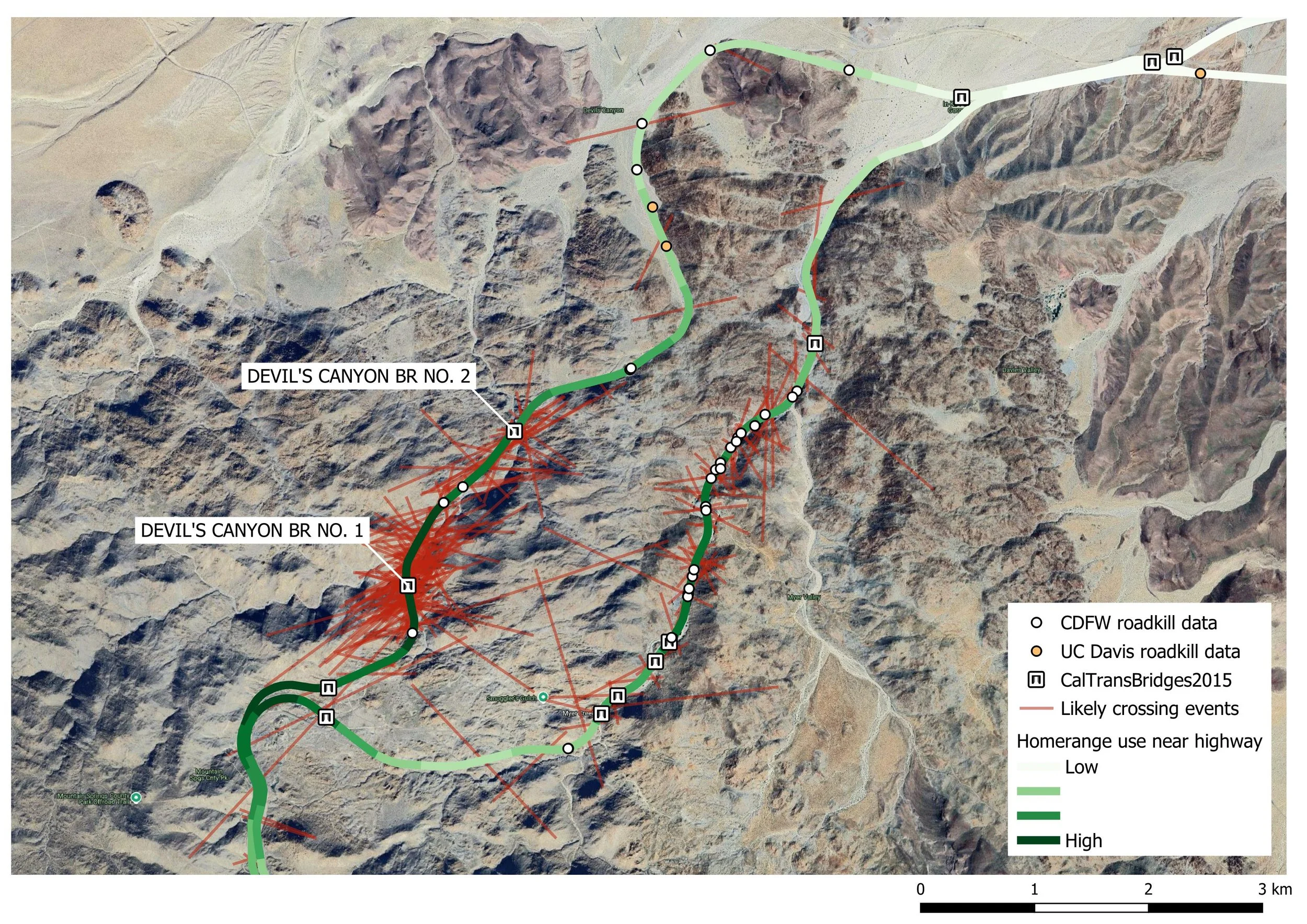

Movement data showed that sheep could successfully cross a westbound section of highway thanks to two large, open underpasses created by two bridges that span a feature called Devil’s Canyon. But on the eastern side, roadkill data from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the UC Davis Road Ecology Center showed the highest concentration of bighorn-vehicle collisions and mortality for I-8.

Selecting and designing a preferred crossing site

The project team weighed a range of factors beyond movement and mortality to determine which sites were preferred for a new crossing through a process developed by the UC Davis Road Ecology Center. Ultimately, the work identified two potential crossing areas on the highway’s eastbound section.

Additional factors the team considered included the presence of other species that might benefit from the crossing, how traffic noise and light could deter animals that approach each section of road, and how roadside topography could affect the ability to construct a crossing.

Caption: Map summary of Peninsular bighorn data considered during site selection for a wildlife crossing structure along I-8. Two existing underpasses beneath the westbound lanes help bighorn cross successfully under I-8 at Devil’s Canyon, while the eastbound lanes have no suitable structures near preferred bighorn habitat. This section of road has the highest concentration of bighorn-vehicle collisions and mortality (Map created by: Christina Aiello, WN California Wildlife Biologist).

The prioritization process helped the team choose the most suitable crossing sites that have the best chance of reducing mortality for bighorn and other important local species. Though the team will design overpasses for both selected locations, they will only move forward with a single design and location after considering factors like constructability and cost.

When designing the crossings, designers seek to mimic bighorn habitat. Bighorn prefer rugged, rocky, and open landscapes where vegetation doesn’t obscure their view of predators. Low, dark culverts or bridges are not attractive — a large, open underpass with rocky slopes, or an open overpass work best. Other species of wildlife have been observed using crossings designed for bighorn.

Caption: Rendering of what an overpass that mimics terrain used by bighorn could look like over I-8. (Bridge design: Sahar Sadegh, UC Davis Road Ecology Center)

Any crossing designs will include roadside fencing on both sides of the crossing to increase the chances that wildlife approaching the highway will reach the crossing.

The two existing underpasses on the westbound side of the highway will also have fencing installed. Though the local ewes could learn to use a new crossing, similar to the underpasses they already use, you inevitably have individuals, especially rams, travelling from more distant areas. The visiting animals are more likely to approach the road at random locations and try to cross traffic — fencing will prevent them from doing so, and hopefully help them find an overpass or underpass.

The road ahead

The next step in the project planning is gathering fine-scale data about each of the two potential crossing sites to inform engineering plans and environmental review.

Like other infrastructure projects, the project must go through an extensive process involving design, construction plans, permits and environmental assessments before any construction begins to ensure that it won’t have a negative impact on other resources in the area.

It’s a long process, but the more wildlife crossings are incorporated into infrastructure planning, the more familiar and streamlined this process will become.